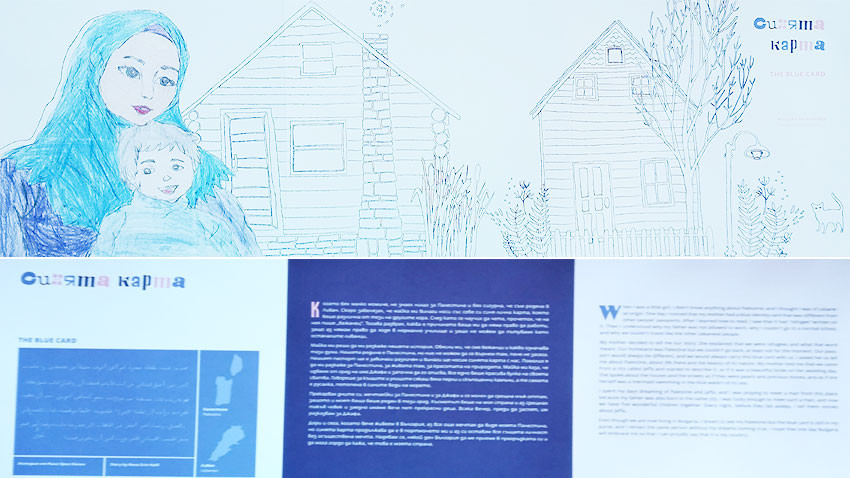

“When I was a little girl I didn’t know anything about Palestine and thought I was of Lebanese origin. One day I noticed that my mother had a blue ID card that was different from other people’s passports. After I learned how to read, I saw it had “refugee” written on it. Then I understood why my father wasn’t allowed to work, why I couldn’t go to a normal school.”

“When I was a little girl I didn’t know anything about Palestine and thought I was of Lebanese origin. One day I noticed that my mother had a blue ID card that was different from other people’s passports. After I learned how to read, I saw it had “refugee” written on it. Then I understood why my father wasn’t allowed to work, why I couldn’t go to a normal school.”

That is how Rana Halil begins her story. Her family have been residing in Bulgaria on a “blue card”, the kind owned by stateless people, people who do not belong to any country. Hers is the only personal story in “Travelling stories” – a collection of stories by children from all over the world, illustrated by child refugees.

“I worked with children living on the territory of refugee centres in the country,” says Martina Raychinova from the Caritas charity organization, thanks to which the collection of stories was able to see the light of day. “The children come and they go, and at one point I got so sad – they left nothing behind except for the photographs we have together and the wonderful stories they had to tell. So we decided we had to do something to remember them by. We first thought it might be drawings, but we wanted to combine them with something coming from their culture, and that was how the idea of children’s bedtime stories they have been told by their parents and grandparents came about. They are stories that have come to us because the children have come to us, and will then go where the children go. That well and truly makes them travelling stories.”

An unorthodox format was chosen for the collection. The 15 stories are printed on triple folded pieces of paper inside a luxury box. On the inside of the left hand page is a photograph of what the children wrote in their own language, the name of the author and the country they come from. In the middle is the story translated into Bulgaria, and on the right – in English.

“We decided to do it like that so as to be able to reach out to a wider readership, but also so that the people living in Bulgaria, who cannot speak Bulgarian, can read the stories,” Martina Raychinova explains. “Part of the drawing on the cover, inspired by the story and drawn by the little artists, has been left empty with the idea that the readers themselves will fill in the blank space, which would help them relate to the story.”

The collection of stories was published for charitable purposes, and the money will be invested to help these families, disadvantaged mothers and children seeking international protection in Bulgaria. The publishers are hoping to make education more accessible to them, to be able to buy the training aids and materials they need, and also to be able to publish the other stories which they couldn’t include in this collection for financial reasons.

“The message this book wants to convey is that we are all the same, no matter where we come from. The moral of the stories is the same as what we teach our own children. The idea is to help Bulgarian society relate to the people residing in the country, and to show that they are no different from us,” says Martina Raychinova, and adds, that despite the efforts of the State Agency for Refugees and the steps taken, people seeking protection in Bulgaria, and especially children, face a great many problems:

“First, they are put up at refugee centres which are isolated in the outskirts of the capital city, so it is not easy for them to get around or to have contacts with the Bulgarian population. They go to school, but what grade they will be registered in depends on their age, even though many of the children have missed school because of war, have no basic knowledge of the language or other subjects. This demotivates them and they drop out of the system of education all too quickly,” Martina Raychinova explains. “It is not an easy thing for them to be admitted to any school, children avoid them, don’t invite them to birthday parties, and after school they go back to the refugee centres. It is important that at home, parents say positive things to their children because children copy the behavior of adults.”

The media can also play an important role, by presenting the subject in a more positive light, because the problem, Martina Raychinova says, comes from the fact that we fear the unknown. But children are the same everywhere, they have the same dreams. What we need to know is that they live amongst us, they go to school, and what they want is to live a steady life, just as we all do.

“I hope that one day Bulgaria will embrace me so that I can proudly say that it is my country,” Rana Halil ends her story. It is the same message Martina Raychinova wants to impart – that people open up their hearts to these children and help them integrate into Bulgarian society.

English version: Milena Daynova

A pink pelican has become a real attraction for the residents of Varna. Hundreds of people have spotted it in the area of the Marine Station in the coastal city and rushed to post his photos on social networks. The pelican is already known there by the..

The prices of Easter goods are rising The Easter meal in the Balkan countries will be more expensive this year, BTA reports. Lamb in Serbia costs about 1,400 dinars (EUR 11.5) per kilogram in supermarkets. On Good Friday, fish..

Residents and visitors to Sofia will have the opportunity to learn more about Bulgarian scientists working in Antarctica and their important role in the exploration of the continent. The exhibition "Antarctic People - Caring for the Earth" by BNR..

International Labor Day on May 1 in the mass consciousness of Bulgarians is often associated with the period of socialism and the grandiose demonstrations..

+359 2 9336 661