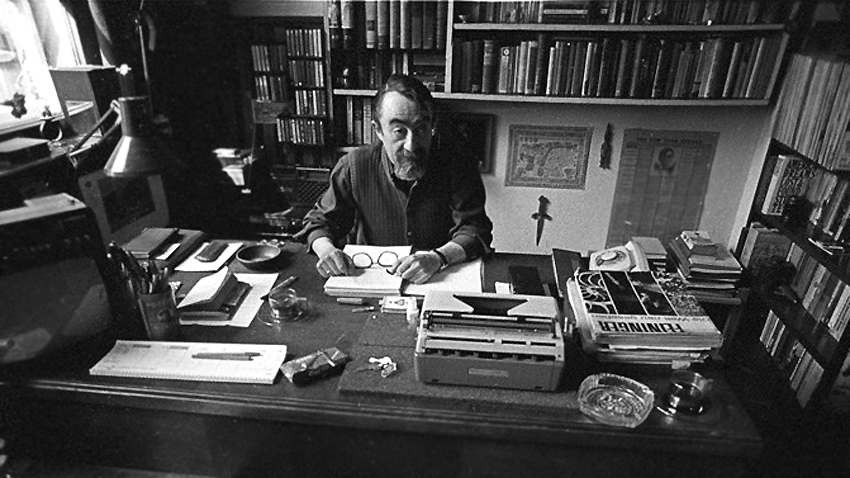

Foremost authors from all corners of the planet came to Sofia for the 5th international meeting of writers in Sofia. The year was 1984. Attention was  riveted on the figure of the forum's honorary chairman Erskine Caldwell. I was 14 at the time. I remember my father going to the Sofia City Library and brining home Caldwell's Fly in the Coffin. That was when from the pages of American literature there appeared the “lonely stooping figure of the silver-haired Erskine Caldwell, that bizarre story-teller that the years never managed to drag through its unifying sieve”, as the translator was to describe him. The crisp phrases of the American Caldwell that reached us in unadulterated Bulgarian are still fresh in my mind. That was my first encounter with translator from the English language Krastan Dyankov, born in 1933, who passed away on 5 March, 1999. He left in Bulgaria's literary treasure-trove his memorable translations of 20th century American classics like John Updike, Arthur Miller, Tennessee Williams, William Saroyan,William Faulkner, as well as a great many literary reviews.

riveted on the figure of the forum's honorary chairman Erskine Caldwell. I was 14 at the time. I remember my father going to the Sofia City Library and brining home Caldwell's Fly in the Coffin. That was when from the pages of American literature there appeared the “lonely stooping figure of the silver-haired Erskine Caldwell, that bizarre story-teller that the years never managed to drag through its unifying sieve”, as the translator was to describe him. The crisp phrases of the American Caldwell that reached us in unadulterated Bulgarian are still fresh in my mind. That was my first encounter with translator from the English language Krastan Dyankov, born in 1933, who passed away on 5 March, 1999. He left in Bulgaria's literary treasure-trove his memorable translations of 20th century American classics like John Updike, Arthur Miller, Tennessee Williams, William Saroyan,William Faulkner, as well as a great many literary reviews.

“From him I learnt how important it is to love the language one works in so as to be able to convey the text one is translating from a foreign into one's own language in the best way possible,” says his son Aleko Dyankov, also a translator. “He was meticulous about the words he used. That was what mattered to him most. He would enrich his own vocabulary by traveling around Bulgaria and collecting words from all parts, dialect words, words typical of every nook and corner, words he would then use in his own translations.”

“From him I learnt how important it is to love the language one works in so as to be able to convey the text one is translating from a foreign into one's own language in the best way possible,” says his son Aleko Dyankov, also a translator. “He was meticulous about the words he used. That was what mattered to him most. He would enrich his own vocabulary by traveling around Bulgaria and collecting words from all parts, dialect words, words typical of every nook and corner, words he would then use in his own translations.”

Krastan Dyankov worked at a time when there was no Internet, so he relied on his huge library that contained all sorts of dictionaries, reference books, encyclopedias. He compiled his own dictionaries of the more unorthodox words different authors use.

“He would work several hours a day when he wasn't on a tight schedule. In the afternoons he would meet up with friends at the writers' café where there was always a noisy crowd - writers, translators, journalists,” Aleko Dyankov says. “He was gregarious, he never shut himself up in ivory towers. There was just one time that I remember when he was translating a collection of American essays when he made his escape - he went to a friend's house in the town of Sopot where he could work undisturbed because he was on a tight schedule then. Otherwise he was a man about town. He would work until the early afternoon and would then enjoy life, pure and simple.”

I ask Aleko whether Krastan himself chose the authors he translated:

“Yes, as much as that was possible in the years of socialism. And after 1989 he never took to translating mass literature - thrillers or whodunits. He never translated books like that. He remained true to his American authors. And he was very choosy - he translated one single story by Hemingway, he has never translated anything else written by him. Though Hemingway was a great writer, my father would say he was not his man.”

Krastan Dyankov was one of the first people to have graduated American studies at Sofia University. His thesis was on Erskine Caldwell, he translated several works by him. He met the man himself at the beginning of the 1960s when Caldwell came to Sofia. In Aleko Dyankov's words that was at a reception in honour of Caldwell at the American embassy or the ambassador's residence, where the two had to go inside the fireplace to be able to talk without being overheard. Another author Krastan Dyankov loved to translate was John Steinbeck. As translator he never dared make any corrections or abridge the text for ideological reasons. What was the price a translator had to pay to avoid censorship in those days?

“Obviously publishing houses were appreciative of his work. There was censorship then, most of all in the choice which authors should be translated at all. But if the word was: Now we translate Steinbeck, no changes were made to the text,” Aleko explains. “My father was very scrupulous that way and he would convey the text just as it was in the original. On the whole he never complained of any of his texts ever having been censored. The only thing he regretted was that for some 15 years Steinbeck was banned in Bulgaria because of his positionon the war in Vietnam. It really hurt my father to know he couldn't translate any of Steinbeck's books, he had so many of them. When that time passed, he translated East of Eden and afterwards he never translated Steinbeck again.”

English version: Milena Daynova

Photos: courtesy of Aleko DyankovThe new Bulgarian film "Don't Close Your Eyes", which premieres in cinemas across the country on January 31, explores the miracles of life and the ability to follow our path without losing faith. In a nutshell, the story revolves around a priest,..

The Sofia MENAR Festival presents films dedicated to art in a selection entitled MENARt, BTA reports. On January 25, at the Cinema House, director Markus Schmidt will personally present his film “Le Mali 70”. After the screening, he..

''The Man Who Could Not Remain Silent'' was nominated for an Academy Award in the category of Best Live Action Short Film. It is a co-production with Bulgarian participation was and was created in collaboration with Katya Trichkova from Contrast Films...

+359 2 9336 661